On today’s show we learn about the Casey’s Larkspur, a critically endangered perennial herb native to the Kyrenia Mountains in northern Cyprus, an island in the east of the Mediterranean sea.

Rough Transcript

Intro 00:05

Welcome to Bad at Goodbyes.

On today’s show we consider the Casey’s Larkspur

Species Information 02:05

The Casey’s Larkspur is a critically endangered perennial herb native to the Kyrenia Mountains in northern Cyprus, an island in the east of the Mediterranean Sea.

Description

They have an erect growth form, reaching heights of up to 3 feet tall. Plants are categorized into three general growth forms, erect, semi-erect, and trailing. In our recent episode about the Graceful Spiderhead we learned about trailing plants that spread horizontally rather than growing upward, they hug the ground with branches that spread out sideways, often laying on the ground itself or growing just above it. Other examples of trailing plants that you may be familiar with are Spider Plants, Pothos, and Petunias. Semi-erect plants have stems that initially grow upright but may bend downward or spread outward, like Ferns, many Rose species, and Forsythia. Plants with an erect growth form, like our Casey’s Larkspur grow upright with a sturdy vertical stem. Examples include, uh trees, sunflowers, and bamboo.

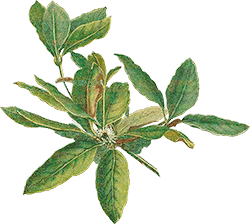

The Casey’s Larkspur’s basal leaves, those are the leaves connected to the lowest section of the stem, are divided into 3-5 lobes, resembling a palm leaf, growing up to 8 inches long, emerging from the base of the plant on long stalks. Farther up the stem, the leaves become smaller and have shorter stalks.

Reproduction

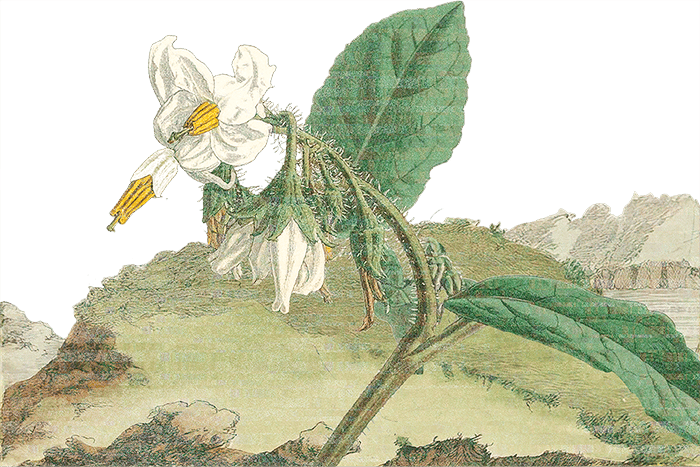

Between May and June, a long, slender stem shoots up from the base of the plant, growing upward and bearing a dozen or more buds that develop into deep violet flowers, covered in fine hairs. Each individual flower has a long spur; a spur is a backward-pointing, hollow, elongated extension of one of the petals, like a long, narrow pouch whose primary function is to hold nectar. The length of a flower’s spur often corresponds to the tongue length of its primary pollinators. So only insects with tongues long enough to reach the nectar at the end of the spur can effectively pollinate the flower. It is an adaptation that increases the efficacy of pollination. By making the nectar accessible only to particular pollinators, the plant increases the chances that its pollen will be successful transferred. In the case of the Casey’s Larkspur, its primary pollinators are thought to be the long-tongued bees native to its habit.

Once successfully pollinated, the flowers produce seed-bearing fruits. I could not find conclusive information on how these seeds are distributed, but given its similarity to other Delphinium in its genus, we can make some hypotheses. Delphinium produce dry fruits. These are pod-like structures that split open when mature, releasing the seeds and so many Delphinium rely on ballistic dispersal, called ballochory, which means the pods explode open, flinging their seeds away from the parent plant. The wind then may carry some of these seeds further, and the slopes of their mountain habitat might also affect dispersal, with gravity helping to carry the seeds downhill.

Habitat

Casey’s Larkspur is exclusively found in a very specific and limited habitat within the Kyrenia Mountains of northern Cyprus. This mountain range runs roughly 100 miles east to west, near the Mediterranean coastline. The Casey’s Larkspur favors the higher elevations in the western portion of these mountains, generally found between 2500 and 3000 feet above sea level, in only two locations, one near Mount Selvili and the other further east near St. Hilarion Castle, together covering a total of less than one and a quarter square miles.

This is an Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forest bioregion. That means that the forests of this region are populated by conifers (cone-bearing trees), sclerophyllous plants, which are a type of vegetation that with hard, leathery leaves, adapted for water-conservation like sage, rosemary, and thyme. And broadleaf trees, like an oak or a maple, and in the case of this Kyrenia Mountain habitat: Mediterranean Cypress, or Golden Oak.

This ecosystem is characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. Summer temperatures can reach highs into the 90s °F, while winter temperatures rarely drop below freezing, usually dipping into the low 40s. Annual rainfall averages around 20 inches, with most of it falling between November and March, and the summer months, June, July and August often seeing little to no rain.

The Kyrenia Mountains developed roughly between 250 million years-20 million years old, pushed up by a collision of the African and Eurasian plates. The landscape is rocky and rugged with steep slopes and cliffs of exposed limestone with shallow soils. The Casey’s larkspur often finds purchase in crevices and fissures within these rocks, its root system growing deep to find moisture on the dry, exposed mountainside.

It shares its habitat with Kykkos Buttercup, Griffon Vulture, Cyprus Sweetvetch, Cyprus Cedar, Bumblebee, Lop-sided Onion, Cyprus Mountain Tea, Long-Legged Buzzard, St. Hilarion Cabbage, Cyprus Giant Fennel, Bonelli’s Eagle, Leaf-cutter bees, Cyprus Crocus, Kyrenia Germander, Cyprus Poppy, Venus Sage, Egyptian Fruit Bat, Cyprus Pink, and many many more.

In The Dream

————

In the dream, as is true in life, to be alone need not be lonely. Like what I wouldn’t give for a day unbothered, quietly stretching my limbs toward the sunlight. In the dream, in plant-time, that is seasons, that’s years untroubled by machine and the hungry, a small protected place, to safely grow. What a rare and tender dream it is, for a place to safely grow.

In the dream.

————

Threats

I do not have the geopolitical knowledge or expertise to properly unpack this, but, Cyprus is a divided island. The south is governed by Greece, and the north, including the Casey’s Larkspur’s habitat, is governed by Turkey following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974. Eventual peace talks led to the establishment of the Cyprus Buffer Zone, a 112 mile long, 1-4 mile wide neutral expanse, between the north and south of the island, overseen by UN peacekeepers. There are areas of the buffer zone which have gone basically untouched by human activity over the last 50 years, with plant and animal life retaking homes and building, and biodiversity thriving. I bring this up: one, because photos from the buffer zone are uncanny and can be beautiful, a reminder of the resilience and potential for rewilding and regrowth of earth’s flora; I encourage you to look up images of this area. And two, this militarized instability has historically complicated research and conservation efforts of Cyprus’s native species, like the Casey’s Larkspur.

The remaining population of the Casey’s Larkspur faces a range of anthropogenic threats. Historically, habitat loss and degradation due to expanding human settlements and infrastructure have reduced its range. And construction projects, like the installation of a military communications array in the late 1970s directly destroyed a large portion of the Mount Selvili subpopulation. Today, limestone quarrying in the Kyrenia Mountains is disrupting the region’s ecosystems

The Casey’s Larkspur is also threatened by overgrazing. Goats grazing in the mountains will eat young larkspur plants, consume the flowers before they’re pollinated, and trample their habitat, hindering growth and reproduction.

And human-induced climate change is forecasted to result in hotter, drier conditions on Cyprus, leading to longer and more frequent drought conditions in this already arid place.

Conservation

The Casey’s Larkspur is legally protected in the EU and one of its subpopulations is within the Karmi State Forest, a designated wilderness.

The Cyprus Wildlife Research Institute has been collecting Larkspur seeds and safe-keeping them in the Cyprus Seed Bank to eventually facilitate their reintroduction into native habitats. In 2022, the Cyprus Seed Bank collected and saved over 2000 Casey’s Larkspur’s seeds.

And in 2023 and 2024 the organization completed a major project to fence around the St. Hilarion subpopulation to protect it from grazing. Their informal observations suggest the successful establishment of new individuals and a possible uptick in the Larkspurs population.

Nevertheless the Casey’s Larkspur has been considered critically endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2006 and their population is generally in decline. Our most recent counts estimate that less than 70 Casey’s Larkspur remain in the wild.

Citations 19:32

“The Biodiversity of Cyprus Island.” Lentini, Alessandro. Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering B 4, no. 3 (2015): 125-131. http://doi.org/10.17265/2162-5263/2015.03.003

Cyprus Wildlife Research Institute – https://v.cwri.net/about-us

Cypress Buffer Zone (somewhat unrelated). The Guardian 20 Jul 2024. Jim Powell – https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2024/jul/20/where-time-has-stood-still-for-50-years-the-un-buffer-zone-in-cyprus-in-pictures

“Establishment of a Plant Micro-reserve Network in Cyprus for the Conservation of Priority Species and Habitats.“ TOP Biodiversity 2010 – Conference Proceedings. Kadis, Costas & Pantazi, Chrisoula & C.T., Tsintides & Christodoulou, Charalambos & Thanos, Costas & Georghiou, Kyriacos & Kounnamas, Constantinos & C., Constantinou & Andreou, Marios & Eliades, Nicolas-George. (2010). – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258132566_Establishment_of_a_Plant_Micro-reserve_Network_in_Cyprus_for_the_Conservation_of_Priority_Species_and_Habitats

“Important Plant Areas Along The Kyrenia Mountains, Cyprus”. Özge Özden Fuller, Mustafa Kemal Merakli, Salih Gücel. Journal of International Scientific Publications: Ecology & Safety vol 10, 349-359 (2016) – https://www.scientific-publications.net/en/article/1001115/

IUCN – https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/61674/3107003

IUCN Mediterranean Islands Plant Specialist Group – “The Top 50 Mediterranean Island Plants. Wild Plants At the Brink of Extinction, and What Is Needed to Save Them.” Bertrand de Montmollin, Wendy Strahm (2005) IUCN. ISBN 2 8317 0832 – https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2005-025.pdf

“Landscape transformation of Cyprus from 1970 through 2070” Ridder, Elizabeth. Doctoral Dissertation. Arizona State University. 2013 – https://hdl.handle.net/2286/R.I.18041

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delphinium_caseyi

If you are interested in learning more about current Casey’s Larkspur conservation efforts, consider following the Cyprus Wildlife Research Institute on Instagram at cypruswildlife – https://www.instagram.com/cypruswildlife/

Music 21:29

Pledge 31:10

I honor the lifeforce of the Casey’s Larkspur. I will commit its name to my record. I am grateful to have shared time on our planet with this being. I lament the ways in which I and my species have harmed and diminished this species.

And so, in the name of the Casey’s Larkspur I pledge to reduce my consumption. And my carbon footprint. And curb my wastefulness. I pledge to acknowledge and attempt to address the costs of my actions and inactions. And I pledge to resist the harm of plant or animal kin or their habitat, by individuals, corporations, and governments.

I pledge my song to the witness and memory of all life, to a broad celebration of biodiversity, and to the total liberation of all beings.