On today’s show we learn about the Centello, a critically endangered flowering magnolia tree native to South America, specifically the municipality of Jardín, in the Andes Mountains in northwest Colombia.

Rough Transcript

Intro 00:05

Welcome to Bad at Goodbyes.

On today’s show we consider the Centello.

Species Information 02:05

The Centello is a critically endangered flowering magnolia tree native to South America, specifically the municipality of Jardín, in the Andes Mountains in northwest Colombia. Its scientific name is Magnolia jardinensis.

Description

The Centello is a tall, canopy tree that generally reaches heights of about 80 feet, though botanists recently found a few individuals estimated to be nearly 200 feet tall. They have a wide straight trunk that can reach 2 feet in diameter, with light grey bark, marked by darker vertical streaks, and lightly pocked with lenticels. Lenticels are small pores that facilitate gas exchange. We went into some detail about lenticels and plant respiration at the top of our June episode about the Kathalekan Marsh Nut, have a listen there if you’d like a bit more info. But basically lenticels help the tree breathe

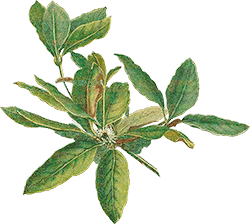

The Centello’s leaves are enormous, growing over a foot in length and 8 inches in width. They have pronounced veins, there is the thick central vein (called the midrib) which branches out into 8-12 diagonal secondary veins, fairly symmetrically on both sides of the midrib; these are called lateral veins and this pattern is called Pinnate Venation. The leaves have an entire margin, which means they have smooth edges. The adaxial side, that is the topside, the upper side of the leaves are a dark rich green and the bottom side, the abaxial side is a much lighter yellow-ish green and is covered in a dense, golden pubescence that is soft, woolly hairs. The leaf-shape is elliptical, so like a long flattened oval, and they have a slightly wavy outline.

Reproduction

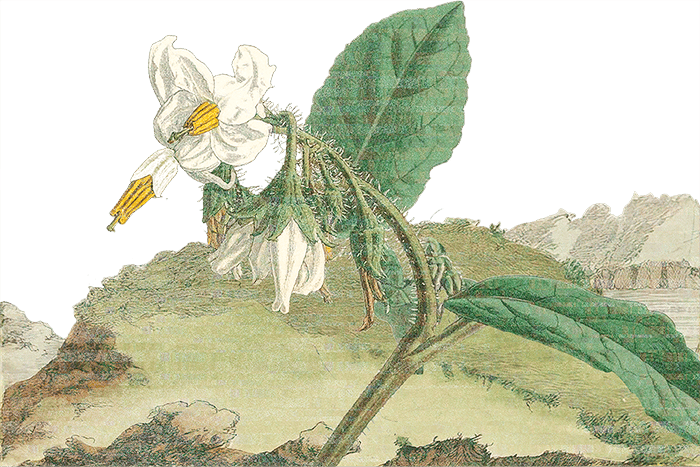

The Centello produces gorgeous creamy white flowers, with eight thick, fleshy, obovate (that’s egg-shaped) petals, each about an inch and a half in length. The Centello is monoecious, it has both male and female reproductive organs in each individual flower. The female productive organs, the pistils, are numerous and form a pyramidal shape in the center of the flower, with the numerous stamen (that’s the pollen producing male reproductive organs) at the structure’s base.

This is a somewhat unusual flower form, but Magnolia are an ancient lineage of flowering plant, with evidence in the fossil record from 95 million years ago. This is the Late Cretaceous period, they lived alongside dinosaurs. And lived before bees, and so their reproductive anatomy evolved adapted for pollination by beetles.

And this is still true today, the Centello is pollinated by the scarab beetle, Cyclocephala concolor.

The tree flowers year-round and once fertilized develops seeds covered in a fleshy, bright red outer seed coat called a sarcotesta. The showy color and energy-rich fruit suggests the seeds are dispersed by animals, but recent observational research finds saplings growing in clusters near their parent plant which implies that their seeds today may instead be distributed via barochory, that is gravity. The seeds simply fall from the parent.

The Centello is a slow growing and long-lived species, taking 10-20 years to reach reproductive maturity, meaning they do not flower for their first 1-2 decades.

It is worth noting that botanists studying the species find very low regeneration, that is poor reproductive success. In the wild, though it flowers in abundance, very little fruit is produced and very few saplings are observed. There is a gap in our knowledge here which wants for further research, but scientists have hypothesized that the tree’s small population may be resulting in self-pollination resulting in nonviable seeds. Or that a decrease in pollinators and/or seed dispersers is affecting regeneration. Or that habitat disruption, resulting in changes to the chemical balance of their already nutrient-poor soils could be affecting germination. Likely it is some combination of all three.

Habitat

The Centello is native to South America, found only near the municipality of Jardín, in the Antioquia department, in northwest Colombia, in the Andes Mountains. This is a high-altitude tropical humid forest habitat, and our tree is found between 1 to 2 miles above sea level, that’s roughly 6000-9000 feet.

These are the cloud forests of the Andes. This is a wildly lush, green overgrown landscape of steep slopes, trees covered in mosses and bathed in cloud cover, that sees up to 150 inches of annual precipitation. Why so much rain? We need to unpack a bit of geography, meteorology and topography.

So, to the east, here near the equator, the Atlantic Ocean gets a ton of sunlight, solar radiation that causes abundant evaporation. Then air currents, called trade winds, blow from east to west, carrying this water vapor inland over the South American continent. Over the Amazon River Basin, and the Amazonian rainforests which contribute more water through evapotranspiration. Evapotranspiration is a combination of evaporation of surface water from the Amazon (the world’s largest river) and transpiration, that’s plants releasing water vapor from their leaves. With an estimated 400 billion trees, the greenery of the Amazon Basin releases massive quantities of water vapor into the atmosphere every day.

The trade winds continue to push this humid air westward, until it reaches the Andes Mountains, a barrier which forces the air upward. And as the humid air rises, it cools; the water vapor condensing to form clouds, and then released as precipitation.

When an air mass is forced from a low elevation to a higher elevation, this is called Orographic lift and here on the eastern side of the Andes Mountains it concentrates humidity, cloud cover, and rainfall, resulting in the rich wet greenery of the Centello’s cloud forest habitat.

The Centello shares its cloudy mountain home with:

Dusky Starfrontlet, Yellow-Breastead Antpitta, Puma, Chestnut Wood-Quail, Neotropical Otter, Gold-Ringed Tanager, Pacarana, Jaguar, Red-Bellied Grackle, Tatama Tapaculo, Black-and-Gold Tanager, Rain Frog, Terrarana Frog, Mountain Pacca, Oncilla, Yellow-Eared Parrot, Colombian Night Monkey, Brown Hairy Dwarf Porcupine, Chestnut-Bellied Flowerpiercer, Humboldt’s Oak, Spectacled Bear, and many many more.

In The Dream

————

In the dream

To ride the winds. To ride the winds 2000 miles, from the ocean to the coast, over the river valley, past that great blue river, over the green blanket, gathering other wanderers, other pilgrims, along the way, swirling into the lowlands, to the foothills and then up, up into the mountain.

We have come to bathe this forest, to slake the thirst of our tallest greenest friends.

What a soft special phenomenon empathy is.

In the dream

————

Threats

Historically, the Centello’s population was profoundly reduced by human exploitation for its wood. Logging.

Subjected to overharvesting and selective logging, which is a commercial practice that targets the largest, straightest, and most valuable individuals to be felled for timber.

The IUCN reports that local loggers have commented that so few individuals remain in the wild that they are no longer a viable commercial target.

And so today, the Centello is threatened by habitat loss and degradation, from human encroachment and land transformation. Their cloud forest ecosystem is now highly fragmented and disturbed. Isolated forest remnants are interrupted by sites clearcut for cattle pastures, coffee and banana plantations, and commercial timber farms, growing pine and eucalyptus, which may be outcompeting the Centello for pollinator and seed disperser attraction.

The tree’s small population is an immediate and future threat. As mentioned, lack of genetic diversity is likely resulting in low seed viable and regeneration. And low population also puts the species at risk for stochastic events, these are random, hard to predict occurrences, which could quickly lead to extinction, like landslides, disease, or extreme weather.

And of course human induced climate change caused by persistent over-reliance on fossil fuels, is an additional threat. Global warming is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather, and is affecting global weather patterns. A shift, for example, in the trade winds that deliver rainfall to the cloud forest, would have a devastating effect on that habitat and the Centello population.

Conservation

Fortunately, most of the Centello population is on a mix of private and governmental protected lands, the El Centello Reserve, the Mesenia-Paramillo Reserve, the Cuchilla Jardin Tamesis Regional Integrated Management District and the Cuchilla San Juan Regional Integrated Management District.

To raise awareness, the municipality of Jardin named the Centello its official tree and added it to the city’s coat of arms.

There are onsite habitat restoration and propagation programs in places. And the Medellín Botanical Garden has three living individuals on its grounds and an offsite cultivation program.

Nevertheless the Centello has been considered critically endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2016 and their population is currently in decline.

Our most recent counts estimate that less than 50 Centello remain in the wild.

Citations 22:44

Calderon, E., Cogollo, A., Rivers, M.C. & Serna-Gonzalez, M. 2016. Magnolia jardinensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T14050337A67514058. – https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T14050337A67514058.en

Jardín Botánico de Medellín – https://www.botanicomedellin.org/descubrenos/investigamos/reserva-biologica-el-centello/

Santa-Ceballos, J. P., Restrepo-Riaño, M. A., Montoya , J. I., Giraldo, J. A., Serna-González, M., & Urrego Giraldo, L. E. (2024). Environmental variables associated with the distribution of two Magnolia species (Magnoliaceae) in the Colombian Andes. Acta Botanica Mexicana, (131). – https://doi.org/10.21829/abm131.2024.2287

Serna-González, M., Urrego-Giraldo, L. E., Santa-Ceballos, J. P., & Suzuki-Azuma, H. (2022). Flowering, floral visitors and climatic drivers of reproductive phenology of two endangered magnolias from neotropical Andean forests. Plant Species Biology, 37(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1442-1984.12351

Serna-González M, Urrego-Giraldo LE, Osorio NW, Valencia-Ríos D (2019) Mycorrhizae: a key interaction for conservation of two endangered Magnolias from Andean forests. Plant Ecology and Evolution 152(1): 30-40. – https://doi.org/10.5091/plecevo.2019.1398

Serna, M., Velásquez, C. & Cogollo, Á. Novedades taxonómicas y un nuevo registro de Magnoliaceae para Colombia. Brittonia 61 (1), 35–40 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-008-9055-7

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnolia_jardinensis

World Conservation Society Columbia – https://colombia.wcs.org/es-es/WCS-Colombia/Noticias/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/21104/Y-POR-QUE-SE-AFIANZO-EN-RISARALDA-UNA-RESERVA-COMO-LA-CUCHILLA-DEL-SAN-JUAN.aspx

World Flora Online (2025): Magnolia jardinensis M.Serna, C.Velásquez & Cogollo. – http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000913301

For more information about Centello conservation please see the Medellín Botanical Garden, that’s Jardín Botánico de Medellín at https://www.botanicomedellin.org/

Music 24:22

Pledge 32:12

I honor the lifeforce of the Centello. I will commit its name to my record. I am grateful to have shared time on our planet with this being. I lament the ways in which I and my species have harmed and diminished this species. I grieve.

And so, in the name of the Centello I pledge to reduce my consumption. And my carbon footprint. And curb my wastefulness. I pledge to acknowledge and attempt to address the costs of my actions and inactions. And I pledge to resist the harm of plant and animal kin and their habitat, by individuals, corporations, and governments.

I forever pledge my song to the witness and memory of all life, to a broad celebration of biodiversity, and to the total liberation of all beings.