On today’s show we learn about the Kathalekan Marsh Nut, a critically endangered flowering tree native to the southwest of India, in the marshlands of the Western Ghats.

Rough Transcript

Intro 00:05

Welcome to Bad at Goodbyes.

On today’s show we consider the Kathalekan Marsh Nut.

Species Information 02:05

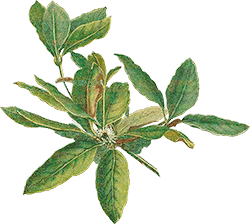

The Kathalekan Marsh Nut is a critically endangered flowering tree native to the southwestern of India, in the marshlands of the Western Ghats. Its scientific name is Semecarpus kathalekanensis, it is a member of the cashew family, and was first described in 2000.

Description

The Kathalekan Marsh Nut is a medium sized tropical evergreen tree that grows between 65 and 95 feet tall. It has smooth and greyish-brown bark marked by raised lenticels, these are little bumps, rounded protruding pores which allow for gas exchange with the surrounding atmosphere; the tree takes in oxygen and releases carbon dioxide.

At first this may seem a little confusing, I think we often think of green plants consuming carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. Um, which is also true. So green plants have two distinct metabolic processes: respiration and photosynthesis.

Plants, like nearly all life, breathe continuously, day and night. This is cellular respiration, a process of taking in oxygen to help break down glucose which releases energy for the plant’s growth, maintenance, and water and nutrient transport. The byproduct is carbon dioxide which is released. So that’s respiration.

Photosynthesis is the process of converting light into chemical energy, stored as glucose. This primarily occurs in leaf cells and requires the presence of light, the intake of carbon dioxide, and the release of oxygen as a byproduct.

So during the day, photosynthesis generally occurs at a much higher rate than respiration. And though during the nighttime, when there is like no light, and photosynthesis is paused, respiration continues, but overall there’s a greater net intake of carbon dioxide and a greater net release of oxygen.

Put simply, green plants, during respiration, “breathe in” oxygen and “breathe out” carbon dioxide, like uh, us. AND, during photosynthesis, “breathe in” carbon dioxide and “breathe out” oxygen. With an overall gas exchange in which more carbon dioxide is consumed and more oxygen is released.

And then to circle back, leaves are the primary site of photosynthetic gas exchange, and the lenticels, on the bark, are the primary site of respiratory gas exchange.

The leaves of the Kathalekan Marsh Nut are huge. Growing in an alternating pattern from the branches from a 4 inch petiole that’s the leaf stalk, the leaf blades can grow over 3 feet in length and roughly 9 inches in width. The leaves are oblong shaped, have a slightly wavy, smooth entire margin, and come to an apex peak, meaning they have a pointed tip on the end.

The Kathalekan Marsh Nut grows specialized root structures called stilt roots and pneumatophores. Stilt Roots grow from the lower trunk and branch downwards into the ground, providing structural support in the soft, waterlogged swampy soil. Pneumatophores (also called knee roots) grow upwards out of the water, once above the water line loop downwards back into the marshbed. These pneumatophores, like the trunk, are also covered in lenticels which again facilitate gas exchange, allowing the roots to “breathe” to acquire oxygen above the water.

In The Dream

————

In the dream,

In the wet blanketing heat, at the shine of the old gods, I breathe with the elder trees. This ancient trade of air, of living, a community of reliances, a negotiation of water and oxygen, a millennia of perpetual promises.

And in the dream, at the shrine, I pray. I recommit myself to the promise. I breathe the same prayer, again and again. Forever and always, for peace.

In the dream.

————

Reproduction

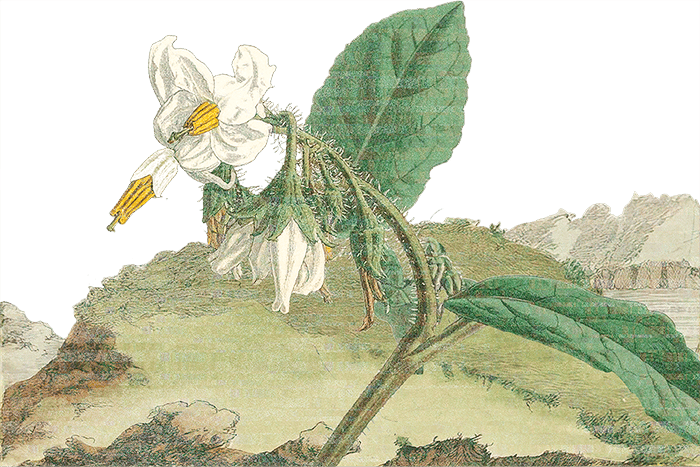

The Kathalekan Marsh Nut is trioecious, meaning that some individuals are male, some are female, and some rare individuals produce both male and female flowers.

From roughly December to February, the greenish flowers grow in elongated branching flower clusters, inflorescences. Male inflorescences can reach roughly a foot and half in length, female inflorescences are shorter, roughly 6 inches in length.

The flowers are pollinated by avian species like the sunbird, the Black Drongo, and the Common Hill Myna, and by the endangered Malabar Tree-Nymph butterfly.

Following successful pollination the female flowers produce a drupe; a stone fruit, like plum, cherry, olive or even cashew with an exocarp (the skin), a mesocarp (the fleshy part) and an endocarp the hard pit or stone which contains the seed. The fruit is kidneyshaped and roughly an inch in size.

Research on Kathalekan Marsh Nut seed dispersal is thin, though anecdotal evidence suggests the Malabar Grey Hornbill, and the endangered Lion-tailed Macaque may play a role, consuming the fruit and distributing the seed in their excrement. Forest mammals like the Malabar Giant Squirrel, Malabar Spiny Dormouse and White-bellied Wood Rat are dispersers of other fruit-bearing species in this habitat and likely may also contribute to marsh nut seed dispersal.

These seeds are “recalcitrant” meaning they will not germinate if dried out, or exposed to cold temperatures. And in the case of the Marsh Nut, seeds are only viable for roughly one week. Making broad dispersal in their habitat challenging.

Habitat

The Kathalekan Marsh Nut is native to western India, in the Uttara Kannada district in state of Karnataka, near the Sharavati River, on the eastern foothills of the Central Western Ghats, a mountain range near the coast of the Indian Ocean. The Marsh Nut grows below 700 ft above sea-level in six discrete subpopulations, occupying a total land area of under 10 sq miles. It is found in highly specialized freshwater marsh forests, called Myristica swamps. These are low-lying, perpetually wet valleys and floodplains, of warm, moist, lush tropical evergreen forests, with trees rising directly out of still or slow moving waters. The canopy is dense and closed, with a dim and humid understory and a forest floor of ferns, sedges, and herbaceous plants adapted to the waterlogged soils.

Myristica swamps are ancient forests, with plant life that can trace lineage to the Late Cretaceous Period, roughly 80 million years ago. These are biodiversity hotspots and play a vital role in carbon sequestration, water filtration, and flood regulation. These swamps act as natural sponges, absorbing water during the rainy season and slowly releasing it during the dry season, helping to regulate water flow and prevent floods.

This is a tropical monsoon climate, with heavy rainfall during the monsoon season, roughly June to September. Annual rainfall exceeds 100 inches per year and can be as high as roughly 200 inches in localized areas. It is hot and humid, summer highs cresting 100°F and winter lows rarely dropping below 60°F.

The Kathalekan Marsh Nut, shares its Myristica swamp home with:

Kanara Nutmeg, Malabar Whistling Thrush, Dancing Frog, Blistering Varnish Tree, Black Drongo, Stream Ruby, Jog Night Frog, Asian Short-Clawed Otter, Malabar Giant Squirrel, Malabar Spiny Dormouse,Paradise Flycatcher, Indian Wild Boar, Tiny Night Frog, Malabar Tree-Nymph, Spindle Tree, Myristica Swamp Frog, White-bellied Wood Rat, Sambar Deer, Crimson-Backed Sunbird, Malabar Trogon, Wild Nutmeg, Gunther’s Supple Skink, Indian Birch, Malabar Pit Viper, White-Bellied Treepie, Malabar Nutmeg, Lion-tailed Macaque, and many many more.

Threats

The primary historic threats to the Kathalekan Marsh Nut have been habitat destruction and fragmentation from human agriculture and infrastructure development. So, land cleared for crops, specifically areca nut plantations; rivers dammed for water use, and highways cutting through the forests.

Today Myristica swamps are highly fragmented into tiny pockets, isolating the remaining Marsh Nut populations.

And today agriculture and development continue to be an issue. Water diversion for agricultural irrigation is lowering the water table and parts of the swamps are seeing dry season desiccation; meaning they are drying up completely. Which of course threatens the marsh nut that relies on that water. Additionally over-grazing and trampling by domestic cattle has been observed to affect Kathalekan Marsh Nut seedlings in particular. The young trees are consumed or destroyed before reaching reproductive maturity.

Regarding infrastructure development: a new proposed highway expansion directly threatens one of the Marsh Nut’s subpopulation.

Ecosystemic balance is also a concern. As mentioned the Marsh Nut relies on an endangered butterfly (the Malabar Tree-Nymph) for pollination, and an endangered monkey (the lion-tailed Macaque) for seed dispersal. Reduction in those populations will then reduce potential reproduction opportunities for the Kathalekan Marsh Nut.

And human induced climate change is a longterm threat. As global warming from continued reliance on fossil fuels affects weather patterns, shifts in monsoon and dry season severities will impact the Marsh Nut’s habitat, leading to further degradation and species loss.

Conservation

Fortunately much of the Kathalekan Marsh Nut’s habitat is on protected land, like the Sharavati Valley Wildlife Sanctuary. Conservation action focused on the endangered Lion-tailed Macaque has indirectly aided the Marsh Nut. Efforts to conserve the macaque’s habitat has brought ecosystem and legal protection to the Marsh Nut as well.

The Kathalekan Marsh Nut also benefits from a fascinating informal protection. Much of its habitat overlaps with sacred sites, and one will find small shrines to local deities tucked into the swamp. And local beliefs discourage the logging or disturbance of these areas. Thus helping preserve the Marsh Nut and its habitat.

Recent work by the College of Forestry, Sirsi is successfully cultivating the Kathalekan March Nut in nurseries off-site and a reforestation program, replanting the species in its native habitat, is underway.

Nevertheless the Kathalekan Marsh Nut has been considered critically endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2021 and their longterm population trend is considered in decline.

Our most recent counts estimate that less than 120, and likely less than 50 reproducing adult Kathalekan Marsh Nut remain in the wild.

Citations 25:44

Information for today’s show on the Kathalekan Marsh Nut was compiled from:

Bioremediation, Biodiversity and Bioavailability 4 (Special Issue I), Global Science Books, 54-68. 4. Chandran, M D & Rao G, Ramachandra & KV, Gururaja & Ramachandra, T V. (2010). “Ecology of the Swampy Relic Forests of Kathalekan from Central Western Ghats, India.” – http://www.globalsciencebooks.info/Online/GSBOnline/images/2010/BBB_4(SI1)/BBB_4(SI1)54-68o.pdf

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. LIFE Trust and Snehakunja Trust. College of Forestry, University of Agricultural sciences Dharwad, Sirsi. 2010-2015. Narasimha Hegde, Shrikanth Gunaga, Andrew “Jack” Tordoff, Medha Hegde, M D Subash Chandran. “Towards ecological restoration of critically endangered freshwater swamps in central Western Ghats: Blending sustainable cultural practices with scientific methods”

https://snehakunja.org/public/assets/pdf/CEPF/Annex%20I%20Participatory%20restoration%20of%20swamps.pdf

Conservation Leadership Programme c/o Birdlife International. 2003- 2004. Tambat, Bhausaheb. “Conservation of the Myristica Swamps - the highly threatened and unique ecosystem in the Western Ghats, India.” – https://www.conservationleadershipprogramme.org/project/conservation-myristica-swamps-india/

Down to Earth 14 Jan 2008. Kirtiman Awasthi. “Revival plan for a disappearing tree”. – https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/revival-plan-for-a-disappearing-tree-3973

Exploring the Mysterious World of Freshwater Swamps: A Documentary. Eco Films. 2023. - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gOxuoxxiAi0

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T175212A1419302. Deepu, S. & Ravikanth, G. 2021. “Semecarpus kathalekanensis.” – https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T175212A1419302.en

Jalplavit Vol. 15 No. 1. Feb.-March 2025. Priya Ranganathan. “Kathalekan Myristica Swamp: A Paradise (Nearly) Lost” – https://pubhtml5.com/kfjv/exmk/Jalaplavit_Feb_March_2025/

Planta Medica v 77. 2011. PJ Hurakadle, MK Parashetti, HV Hegde. “Antimicrobial studies on Semecarpus kathalekanensis” – https://doi.org10.1055/s-0031-1282910

Restoration Methodologies and Conservation Strategies Conference. Vasudeva R, Raghu H.B, Suraj P.G, Uma Shaanker R, Ganeshaiah K.N. 2002 “Recovery of a Critically Endangered Fresh-Water Swamp Tree Species of The Western Ghats” – https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/lake2002/proceedings/8_2.html

Wetlands Ecology and Management. v. 30. Ranganathan, Priya & Ravikanth, Gudasalamani & N A, Aravind. (2022). “A review of research and conservation of Myristica swamps, a threatened freshwater swamp of the Western Ghats, India”. – https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-021-09825-5

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_Ghats

For more information about Kathalekan Marsh Nut and Myristica swamp conservation see the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment at https://www.atree.org/projects/roadmap-to-restoration-developing-an-ecologically-sensitive-restoration-model-for-myristica-swamps-in-karnataka/

Music 27:55

Pledge 33:17

I honor the lifeforce of the Kathalekan Marsh Nut. I will commit its name to my record. I am grateful to have shared time on our planet with this being. I lament the ways in which I and my species have harmed and diminished this species. I grieve.

And so, in the name of the Kathalekan Marsh Nut I pledge to reduce my consumption. And my carbon footprint. And curb my wastefulness. I pledge to acknowledge and attempt to address the costs of my actions and inactions. And I pledge to resist the harm of plant and animal kin and their habitat, by individuals, corporations, and governments.

I forever pledge my song to the witness and memory of all life, to a broad celebration of biodiversity, and to the total liberation of all beings.