On today’s show we learn about the Erubia, a critically endangered flowering shrub native to the US island territory of Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Sea.

For more information about conservation in Puerto Rico, please visit Para la Naturaleza at https://paralanaturaleza.org

Rough Transcript

Intro 00:05

Welcome to Bad at Goodbyes.

On today’s show we consider the Erubia.

Species Information 02:05

Erubia is a critically endangered flowering shrub native to the US island territory of Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Sea. Its scientific name is Solanum ensifolium and it was first described in 1852.

Description

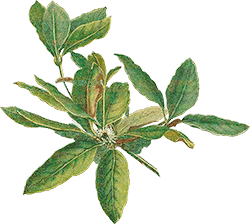

Erubia is a perennial suffrutescent herb. Perennial, persisting over multiple years and reproduction cycles; and suffrutescent herb is a plant with a woody base but with herbaceous (non-woody) soft upper stems. They present as a shrub or sometimes as a small tree occasionally even reaching heights of 18 feet.

The woody bark is reddish-brown, the herbaceous stems are green and both are covered in trichomes, these are small white-ish hairs. Its leaves are lanceolate, a narrow oval shape that tapers to a point at each end, roughly 7 inches long and 2 inches wide, with an entire margin, meaning it has smooth edges. Some Erubia develop prickles on their leaves, these are roughly half inch spikes that grow from the leaves’ mid-rib; that is the center vein in the middle of the leaf. The trichomes and the prickles are defensive adaptations, the small hairs discourage feeding by smaller animals, like insects and the prickles deter larger grazers like rodents.

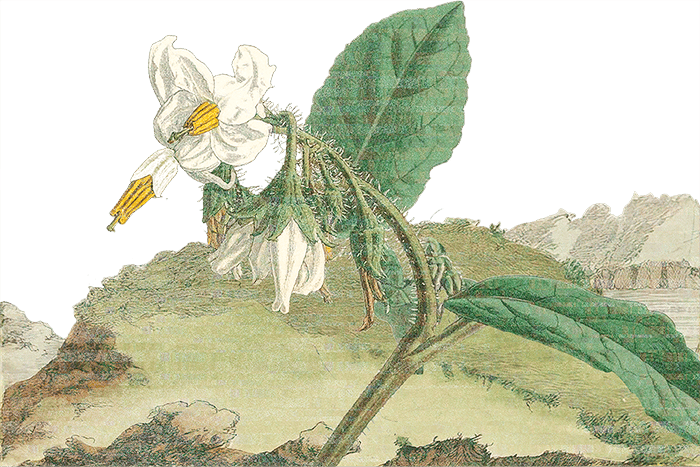

Their flowers are shaped like a five pointed star, with 5 long, skinny white petals that bend backward toward the stem and away from the reproductive organs at the center of the flower. The flowers are hermaphroditic, meaning each flower contains both male reproductive organs (stamen, anthers) and female reproductive organs (pistil, style, ovaries). The pollen-holding anthers are yellow, about a quarter inch long, and fused into a cone-like tube shape, with the female style inside at the center, just long enough to poke out. The inside of the tube is also filled with trichomes, more tangled protective hairs.

Reproduction

This somewhat unusual flower form is related to its pollination. Erubia is buzz pollinated. So, in like 90% of all flowers, the anthers release pollen easily, a light touch the brush of a leg or feather. But roughly 10% of all flowers, like our Erubia, and more common species like tomatoes and blueberries, have poricidal anthers; pollen is held tightly within their tube-structure and they have only small pores or a slit at their very tip. To release the pollen, a pollinator must physically shake the anther at a specific high frequency. So bees hold the flower with their mandibles and legs then rapidly contract their flight muscles, but without flapping their wings. This generates vibrations that travel through the bee’s body into the flower, causing the anthers to resonate, shaking pollen out of the pores in a small cloud, coating the bee’s fuzzy body. Then as the bee moves to other flowers, it transfers this pollen; this is buzz pollination.

Erubia is self-incompatible. This means that an individual plant cannot fertilize itself; it needs pollen from a genetically distinct individual to produce viable seeds.

Once pollinated, the Erubia develops a round shiny black berry, about a quarter inch in diameter holding 10 to 20 small pale yellow seeds, which are likely dispersed by birds.

In The Dream

————

In the dream,

A speck of pollen is a possible future, is optimistic, is a gesture of hopefulness.

With spines and tangles I protect this treasured promise.

And yet, though perhaps begrudgingly, if you hold me, and sing into my depths, I will release it, a cloud of sweet bright aspirations entrusted to your skybound journey.

Fly well, small friend; there is more riding on you than you know.

In the dream.

————

Habitat

Erubia is native to the US island territory of Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Sea, in the southeast of the island at the very top of the Municipality of Salinas, near the mountain peaks Las Piedras del Collado in the Sierra de Cayey mountain range.

The remaining population is found only in an area of less than one square mile, roughly 1000 to 3000 ft above sea level. These are rocky steep sloped peaks formed by ancient volcanic activity, of basalt, and volcanic sandstone and siltstone. It is humid, damp and lush, an evergreen subtropical wet forest, a mix of old growth vegetation and secondary growth forests, land now rewilding after centuries of human intrusion.

Summer temperatures in this region reach into the low 90s°F, and winter lows rarely drop below 60°F. Precipitation averages roughly 60 inches per year.

Erubia shares its island home with:

Puerto Rican Broad-Winged Hawk, Puerto Rican Emerald, Mountain Coquí, Palo de Ramón, Ponce Mayten, Sierra Palm, Puerto Rican Woodpecker, Adelaide’s Warbler, Mongoose, Roble De Sierra, Uvillo, Scarlet Star, Granadillo Bobo, Bertero’s Tufted Airplant, Red Fig-Eating Bat, Puerto Rican Vireo, Yellow-Chinned Anole, Puerto Rican boa, Black Rat, Puerto Rico Lacebark, Puerto Rican Twig Anole, and many many more.

Threats

Historically, human habitat exploitation and destruction significantly reduced the Erubia population. Vast areas of Puerto Rico’s mountain forests were felled: logged for charcoal and wood production, clear cut for agriculture (specifically coffee plantations) and transformed to pastureland for domesticated cattle grazing.

Relatedly, Erubia itself was targeted for deliberate eradication by farmers. Our plant’s sharp spines were perceived as a danger to livestock, and landowners purposefully removed and destroyed Erubia growth.

Today, human encroachment upon and reduction of habitat continues to threaten the species, but the main concern now is simply its low population. Low population puts Erubia at risk for stochastic events, these are random unpredictable occurrences that could wipe-out the remaining population all in one go. So a landslide, a severe wildfire, a hurricane.

Low population has also resulted in a genetic bottleneck. As mentioned, Erubia cannot self-pollinate nor reproduce asexually via cutting or clone; pollen from a genetically distinct individual is required for viable seed production. Low population and lack of genetic diversity within that population is imperiling their natural regeneration.

Human induced climate change is an imminent threat. Changing weather patterns resulting from global warning, increases the risk of extreme weather, making stochastic events, like wildfire and hurricane, more likely.

Conservation

Fortunately, Erubia is legally protected, locally (by the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico), federally (by the U.S. Endangered Species Act) and internationally by the IUCN.

And in 2000, this region of the Sierra de Cayey mountains was declared a protected wilderness, the Las Piedras del Collado Nature Reserve.

Additionally, offsite conservation programs are in place. Erubia seeds are in safe offsite storage at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens Seed Bank. And, Eastern Connecticut State University has a living collection where researchers have manually facilitated cross-pollination to produce viable seeds and cultivate new individuals.

In 2024, seedlings from the Eastern Connecticut State collection were sent to Puerto Rico to be reintroduced into their natural habitat.

Nevertheless, Erubia has been considered critically endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2012 and their population is currently in decline.

Our most recent counts estimate that less than 200 Erubia remain in the wild.

Citations 19:24

Information for today’s show about the Erubia was compiled from:

Eastern Connecticut State University – https://www.easternct.edu/news/_stories-and-releases/2025/01-january/easterns-greenhouse-is-a-sanctuary-for-imperiled-plants.html

Gann, G.D. 2024. Solanum ensifolium. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T212065930A253642712. – https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T212065930A253642712.en

Graham, M.R., Kaur, N., Jones, C.S. et al. A phoenix in the greenhouse: characterization and phylogenomics of complete chloroplast genomes sheds light on the putatively extinct-in-the-wild Solanum ensifolium (Solanaceae). BMC Plant Biology 25, 320 (2025). – https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06338-8

The Institute for Regional Conservation – https://www.regionalconservation.org/ircs/database/plants/PlantPagePR.asp?TXCODE=Solaensi

Jankauski Mark, Ferguson Riggs, Russell Avery and Buchmann Stephen. 2022. Structural dynamics of real and modelled Solanum stamens: implications for pollen ejection by buzzing bees. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. Volume 19 Issue 188. 1920220040 – http://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2022.0040

National Science Foundation’s Solanaceae Source – https://solanaceaesource.myspecies.info/content/solanum-ensifolium

Pascarella, John & Aide, T. Mitchell & Serrano, Mayra & Zimmerman, Jess. (2000). Land-Use History and Forest Regeneration in the Cayey Mountains, Puerto Rico. Ecosystems. 3. 217-228. – https://doi.org/10.1007/s100210000021

Rosario, Lumariz Hernandez, Juan O. Rodríguez Padilla, Desiree Ramos Martínez, Alejandra Morales Grajales, Joel A. Mercado Reyes, Gabriel J. Veintidós Feliu, Benjamin Van Ee, and Dimuth Siritunga. “DNA Barcoding of the Solanaceae Family in Puerto Rico Including Endangered and Endemic Species.” Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 144, no. 5 (2019): 363–374. – https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS04735-19

Strickland-Constable, R., Schneider, H., Ansell, S.W., Russell, S.J. and Knapp, S. (2010), Species identity in the Solanum bahamense species group (Solanaceae, Solanum subgenus Leptostemonum). Taxon. 59. 209-226. – https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.591020

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service – https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/817

For more information about conservation in Puerto Rico, please visit Para la Naturaleza at https://paralanaturaleza.org

Music 21:02

Pledge 26:42

I honor the lifeforce of the Erubia. I will commit its name to my record. I am grateful to have shared time on our planet with this being. I lament the ways in which I and my species have harmed and diminished this species. I grieve.

And so, in the name of the Erubia I pledge to reduce my consumption. And my carbon footprint. And curb my wastefulness. I pledge to acknowledge and attempt to address the costs of my actions and inactions. And I pledge to resist the harm of plant and animal kin and their habitat, by individuals, corporations, and governments.

I forever pledge my song to the witness and memory of all life, to a broad celebration of biodiversity, and to the total liberation of all beings.