On today’s show we learn about the Mulanje Cedar, a critically endangered conifer tree native to the African nation of Malawi, specifically to Mount Mulanje in the southeast.

For more information about Mount Mulanje conservation, please see the Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust at https://mountmulanje.org.mw

Rough Transcript

Intro 00:05

Welcome to Bad at Goodbyes.

On today’s show we consider the Mulanje Cedar.

Species Information 02:05

The Mulanje Cedar is a critically endangered conifer tree native to the African nation of Malawi, specifically to Mount Mulanje in the southeast near Mozambique. Its scientific name is Widdringtonia whytei and it was first described in 1894.

Description

The Mulanje Cedar is a tall evergreen conifer that can reach heights of 160 feet, with a trunk that can reach 5 feet in diameter.

Their growth form changes as they mature. In juvenile stages the tree is pyramid-shaped, imagine a classic christmas tree, a form adapted for more rapid vertical growth to compete for light. But then as the Mulanje Cedar matures and reaches the forest canopy, sometime roughly aged 25-50, branches begin to spread outward into an expansive, broad flat-topped crown, adapted now to better collect moisture from mist and fog.

We see a comparable shift in the cedar’s leaf form. Juvenile leaves are bright green, long and needle-like, again, adapted to maximize light absorption, and also as defense against grazers. But later adult foliage is scale-like, tiny diamond shaped leaves layered tightly on the branchlets, looking a bit like a braided rope, matte olive green in coloration. When the tree is tall enough to be beyond the reach of grazers, and with a crown spread enough to get ample light, the leaves shift to this scale-like form to minimize water loss, and collect fog.

Mist and fog are frequent in the higher elevations of Mount Mulanje, and the Mulanje Cedar is adapted to utilize this atmospheric moisture. The leaves and spread crown act as condensation surfaces. Atmospheric moisture (fog, clouds, mist) condenses on the foliage and drips down to the tree’s roots. This is called “fog drip”, providing crucial additional water during the dry season.

The bark of mature Mulanje Cedar is very thick, as much as an inch and a half in depth. It is brown-ish grey in color with a soft, spongy, texture. The Mujane Cedar is somewhat fire-adapted and this thick spongy bark is a thermal insulation that protects the tree’s vital interior from lethal temperatures, allowing it to survive low-intensity wildfires. That said, this thickened bark takes about 50 years to form and harden, so juvenile cedar remain very vulnerable to wildfire.

Reproduction

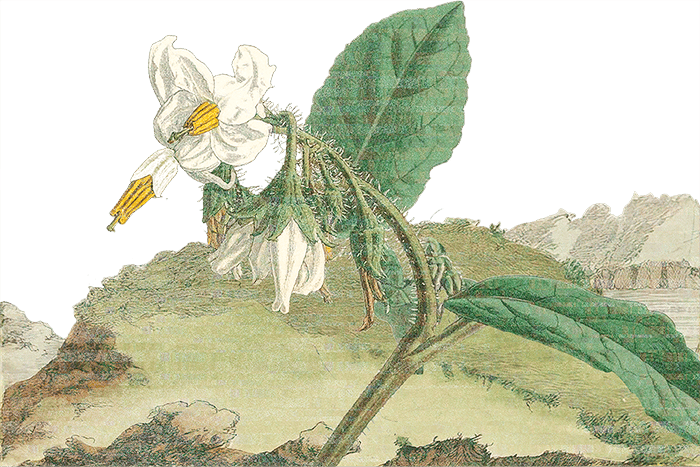

The Mulanje Cedar is monoecious, meaning that individuals bear both male pollen-producing cones and female seed-producing cones. Male cones are small and numerous, growing at the tips of the branches. They are yellowish-green to yellowish-brown, about a quarter of an inch in length, each bearing roughly 25 pollen sacs, which release pollen that is spread by the wind. Female cones are larger, woody, and round, roughly three quarters of an inch in diameter, dark brown to reddish-brown in coloration, and hold roughly 3-10 seeds. The seeds are flat, ovoid (that’s egg shaped), about quarter inch in length, dark-brown to black in color and winged. Seeds are dispersed by anemochory (that’s wind dispersal).

The female cones are also somewhat serotinous. Serotinous describes how a cone will remain closed delaying seed dissemination for an extended period after fertilization, often only opening following a trigger event like fire. Many fire adapted conifers exhibit this trait, holding their seeds until the presence of high heat. But the Mulanje Cedar is only semi-serotinous. Some of their cones will gradually open, releasing seeds. But some remain closed on the tree, only released following fire. The fire’s heat splits the cone open, dropping seeds into a now nutrient-rich ash and soil bed, free of competition.

The Mulanje Cedar is slow growing, taking roughly two decades to reach reproductive maturity. It can live for several hundred years.

————

In The Dream

In the dream,

To live for several hundred years,

to cast shadow over generations,

to gather mist to water innumerable lifecycles in the understory,

to offer uncountable seeds to the wind.

To be a living symbol, totemic, tall above the peaks and plains,

and also though to simply live.

It is enough to just grow,

to be witness to fire and storm, to drink light and fog, to cone and open.

There is a humility and dignity in surviving.

In the dream.

————

Habitat

The Mulanje Cedar is native to southeast Malawi, specifically to Mount Mulanje, a granite inselberg. An inselberg is a steep-sided isolated formation, mountain or plateau that rises abruptly above surrounding plains. Roughly 130 million years ago an intrusion of magma pushed up the earth’s crust here and in the time since the surrounding rock eroded away, leaving behind the erosion resistant granite resulting in this isolated expanse of high elevation.

This is a high-altitude rolling grassland, roughly a mile and half above sea level, intersected by deep forested ravines and pocked with even higher peaks. This is an Afromontane forest biome that sees over 100 inches of annual precipitation, with distinct wet and dry seasons: wet season is roughly November–April, dry season is May–August. The warm wet season sees highs averaging in the 80s°F, dry season lows dip into the 30s°F with occasional frosts.

Our Mulanje Cedar is found at roughly 1-1.25 miles elevation, in rocky, shallow, acidic soil, often in ravines, gorges, and valleys where moisture collects, where the soil is a bit deeper, and where the topography, nestled between granite rock faces, provides some protection. The Mulanje Cedar can thrive across the upper plateau of the inselberg, an area of roughly 75 square miles.

The Mulanje Cedar shares this mountain home with:

Blue Duiker, Cape Ash, Broadley’s Grassland Frog, Mulanje Mountain Chameleon, Lemonwood, Onionwood, Klipspringer, Tshiromo Frog, Mulanje Red Damselfly, King Dwarf Gecko, Parasol Tree, Ruo River Screeching Frog, Mitchell’s Flat Lizard, East African Yellowwood, Mesic Four-Striped Grass Rat, Malawi Stumptail Chameleon, Yellow-throated Apalis, Black Ironwood, Cape Beech, and many many more.

Threats

Historically, the Mulanje Cedar population was dramatically reduced by human over-exploitation for timber. The cedar’s wood is durable, termite- and fungus-resistant, has a lovely pale red hue, a straight grain, and even smells nice. As such it has been used for hundreds of years for construction, fenceposts, boat-building, even fine woodworking. By the middle of the 20th century, commercial industrial logging had removed the vast majority of the old-growth cedar.

Today, though the tree is protected, illegal logging persists, with poachers targeting the few remaining mature trees in the most remote ravines.

Fire is also a threat. Though the Mulanje Cedar is somewhat fire-adapted, it is not adapted to today’s fire frequency. Historically the natural fire cycle on the mountain was likely infrequent, giving our trees the roughly 50 years needed to grow their protective bark before the next burn. But today, fires are anthropogenic, human-caused, started by poachers, charcoal burners, or for land-clearing, occurring almost annually. And so these frequent fires kill juvenile saplings before reaching reproductive age and grow their fire-resistant bark.

The result is a kind population squeeze: tall older reproducing trees are felled for timber and young trees burn, leaving no successor generations.

Additionally, human introduced invasive species threaten the Mulanje Cedar. The Giant Cypress Aphid, an insect that feeds on the cedar’s sap, was introduced to Africa in the 1980s and continues to impact the cedar population. And invasive plants like Himalayan Raspberry and the Mexican Pine, compete with the Mulanje Cedar for resources.

Conservation

Fortunately all of the Mulanje Cedar’s remaining population grows within the Mulanje Mountain Forest Reserve, a protected wilderness. And a collaboration between the Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust, the Forestry Research Institute of Malawi, and Botanic Gardens Conservation International, has initiated extensive conservation programs.

Key to these programs is collaboration with local residents. Conservationists acknowledge that the root cause of the illegal logging is poverty, and so any protective efforts have to consider these economics.

And so, community nurseries were established around the base of the inselberg, staffed by locals, to cultivate seedlings for restoration. Locals were then hired to plant these seedlings across the upper plateau. This was a massive undertaking, with over 500,000 seedlings replanted, creating over 1000 jobs in nursery management, planting, and forest monitoring.

Fire-management programs are also in place, with local residents employed to dig fire-breaks to prevent the spread of wildfire to newly replanted seedlings.

And there is an offsite cultivation program, at the Inala Reserve in Tasmania Australia, to germinate seeds and cultivate saplings for a living offsite population and to produce viable seedlings to share with other botanic gardens and eventually help reforest Malawi.

Nevertheless the Mulanje Cedar has been considered critically endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2013 and their population is currently in decline.

Our most recent counts estimate that less than 49 Mulanje Cedar remain in the wild.

Citations 23:53

Information for today’s show about the Mulanje Cedar was compiled from:

Bayliss, Julian, Steve Makungwa, Joy Hecht, David Nangoma, and Carl Bruessow. “Saving the Island in the Sky: The Plight of the Mount Mulanje Cedar Widdringtonia Whytei in Malawi.” Oryx 41, no. 1 (2007): 64–69. – https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605307001548

Burger, Niel. “Disturbance ecology and size-class structure of the Mulanje cedar of Malawi, Widdringtonia whytei, and associated broadleaved forest.” Botany honours project 2010. University of Cape Town. – http://hdl.handle.net/11427/24397

Chanyenga, Tembo F., Coert J. Geldenhuys, and Gudeta W. Sileshi. “Effect of Population Size, Tree Diameter and Crown Position on Viable Seed Output per Cone of the Tropical Conifer Widdringtonia Whytei in Malawi.” Journal of Tropical Ecology 27, no. 5 (2011): 515–20. – https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467411000204

Chanyenga, T., Shaw, K. & Mitole, I. 2019. “Widdringtonia whytei.” The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T33216A126090798. – https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T33216A126090798.en

CNN. “Saving Malawi’s Mulanje Cedar.” October 2025. Inside Africa S21 E21. – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTNGckdP7kk

Earle, Christopher J., ed. “Widdringtonia whytei.” The Gymnosperm Database. February 10, 2025. – https://conifers.org/cu/Widdringtonia_whytei.php.

Farjon, A. 2019. “Widdringtonia whytei.” Threatened Conifers of The World – https://threatenedconifers.rbge.org.uk/conifers/widdringtonia-whytei

Frank, Fred & Mwabumba, Lusayo & Mhango, Jarret & Missanjo, Edward & Kadzuwa, Henry & Likoswe, Michael. (2023). “Genetic and Phenotypic Parameters for Growth Traits of Widdringtonia whytei-Rendle Translocation Provenance Trials in Malawi.” Journal of Global Ecology and Environment. Volume 17, Issue 4. 32-48. – https://doi.org/10.56557/jogee/2023/v17i48222

Martin, Emma, and Burgess, Neil. “Mulanje Montane Forest-Grassland.” One Earth. September 23, 2020. – https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/mulanje-montane-forest-grassland

Mitrani, Leila. 2017. “Reproduction and establishment of two endangered African cedars, Widdringtonia cedarbergensis and Widdringtonia whytei.” Masters Thesis. University of Cape Town. – http://hdl.handle.net/11427/25431

Missanjo, Edward & Frank, Fred. (2015). “Restoration and Survival Trend of Widdringtonia whytei Forest at Chambe Basin, Mulanje Mountain.” Journal of Basic and Applied Research International (JOBARI). 3 (2). 54-58. – https://ikprress.org/index.php/JOBARI/article/view/3135

Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust – https://mountmulanje.org.mw

Pauw, C. Anton and Linder, Peter H. “Tropical African cedars (Widdringtonia, Cupressaceae): systematics, ecology and conservation status.” Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 123, Issue 4, April 1997, Pages 297–319. – https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.1997.tb01421.x

Smith, Paul. “Saving Malawi’s National Tree.” BGjournal 12, no. 2 (2015): 34–36. – https://www.jstor.org/stable/24811438

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Widdringtonia_whytei

For more information about Mount Mulanje conservation, please see the Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust at https://mountmulanje.org.mw

Music 25:52

Pledge 32:02

I honor the lifeforce of the Mulanje Cedar. I will commit its name to my record. I am grateful to have shared time on our planet with this being. I lament the ways in which I and my species have harmed and diminished this species. I grieve.

And so, in the name of the Mulanje Cedar I pledge to reduce my consumption. And my carbon footprint. And curb my wastefulness. I pledge to acknowledge and attempt to address the costs of my actions and inactions. And I pledge to resist the harm of plant and animal kin and their habitat, by individuals, corporations, and governments.

I forever pledge my song to the witness and memory of all life, to a broad celebration of biodiversity, and to the total liberation of all beings.