On today’s show we learn about the Madagascar Banana, a critically endangered flowering plant native to the island nation of Madagascar roughly 250 miles off the southeastern coast of the African mainland.

Rough Transcript

Intro 00:05

Welcome to Bad at Goodbyes.

On today’s show we consider the Madagascar Banana.

Species Information 02:05

The Madagascar Banana is a critically endangered flowering plant native to the island nation of Madagascar roughly 250 miles off the southeastern coast of the African mainland. Its scientific name is Ensete perrieri and it was first described in 1909.

Description

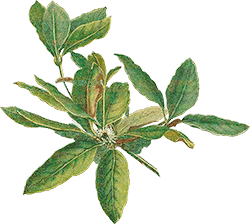

The Madagascar Banana, is a very large flowering herbaceous plant, that can reach heights up to twenty feet. Like other banana species, the Madagascar Banana is technically not a tree, as they do not produce a woody trunk or branches, they are in fact a really big herb.

So what looks like their trunk is actually a “pseudostem,” a thick central pillar formed not by wood, but by layers of leaf sheaths packed tightly together. So their leaves have two main parts, the leaf blade, large broad waxy green fronds with a bright yellow central vein (the mid-rib), and the sheath, the long one inch thick base of the leaf, that wraps around the stem. So new leaves grow from the top, wrapping their sheaths tightly around the ones already there, building up layers around the stem.

The Madagascar Banana is drought-deciduous, meaning that they shed their leaf blades during the dry season. This is to prevent water loss. So the green blades die back and fall away, but the thick, moisture-rich sheaths persist. So at the base, we’ll see dried, brown sheaths from previous growth cycles, then just above those are newer short, green sheaths without leaf blades, and then at top, the newest green sheaths of the current growing year emerge with actively photosynthetic leaf blades.

This seasonal buildup of leaf sheaths can produce a pseudostem as large as 8 feet in diameter at the base that tapers to about 2 feet in diameter at the crown, a strong structure that allows for heights of nearly 20 feet without the plant having any “true” wood.

The Madagascar Banana is passively pyrophytic, meaning it is fire tolerant, able to resist the effects of fire. This pseudostem, which has high water content and is very thick, insulates and protects the plant’s main stem at its center. So fire may scorch or burn the outer layers of the pseudostem but the main stem, responsible for new growth, is preserved, allowing the plant to continue to flourish after wildfires.

Reproduction

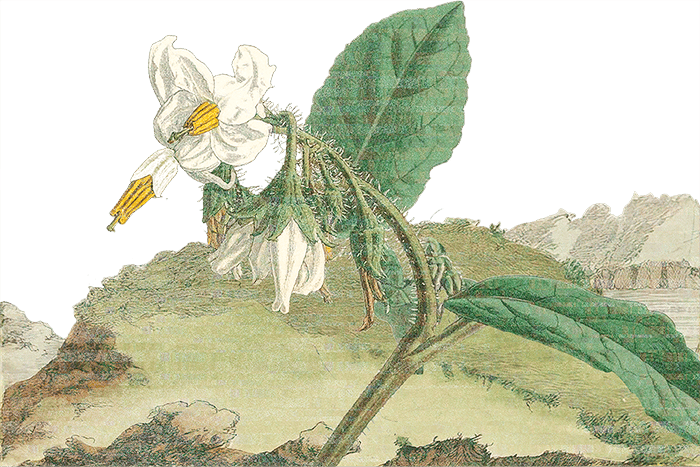

The Madagascar Banana is monocarpic, meaning that it flowers and seeds, only once and then dies. In this kind of reproductive strategy, a plant grows and stores resources throughout its life for a singular and final blossoming. In the case of the Madagascar Banana, it takes between 5-15 years to reach maturity and then the plant shifts from producing new leaves to producing a massive flower cluster that can weigh up to 8 pounds. This inflorescence is a spiral of roughly 60 bracts, protective leaf-like structures that are green at the base then gradient through yellow, pink, lavender, to a deep violet at their tips. Tucked inside the bracts are roughly 20 flowers with pink-ish white petals. The flowers produce yellow, round pollen with a warty texture, a bumpy surface likely adapted to stick to fur.

Available literature speculates that the Madagascar Banana is possibly pollinated by fruit bats or lemurs, though I could not find direct observational confirmation of this.

Once pollinated the Madagascar Banana bears fruit, it makes bananas, producing a massive fruit cluster, an infructescence that can weigh up to 75lbs, containing 200 fruits. The fruit is cylindrical, 4-5 inches in length, with a yellow outer skin, looking like a kind of squat version of our common domesticated bananas.

But the fruit’s flesh is high in tannins, and incredibly bitter; totally inedible for humans, and as such, the species has never been cultivated.

The seeds are black, relatively large, like a quarter to a half inch in diameter, and encased in a hardened outer layer called a testa.

The seeds are distributed by endozoochory, so, transported via the digestion of animals. And again, though observationally unconfirmed, we think lemurs consume the fruit. Then the seeds move through the lemur’s acidic digestion system which wears down the testa, the seed coat, and then are deposited via the lemur’s excrement, prepped for germination.

In The Dream

————

In the dream,

I am hosting a dinner party for my neighbors, cooking all day, an elaborate, extravagant meal. This is of course a terrible idea, my apartment is tiny, my stove is tiny, my dinner table is tiny. But I’m putting my all into it. Chopping, stirring, baking, spicing, frantic to create a fabulous feast. The table is set, the food is plated, I am ready. And yet, when it is time, no one arrives.

In the dream.

————

The Madagascar Banana is native to three locations on the island of Madagascar, in the Indian Ocean off the African coast. Though once more widespread, today they are found mainly in the west in the Antsalova District, within the Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park.

Tsingy are geological formations: steep, sharp limestone pinnacles, stone needles, formed over roughly 200 million years, beginning with the accumulation of calcite minerals at the bottom of a Jurassic era lagoon. Tectonic activity over the following 150 million years lifted the region, while acidic rainwater eroded the softer calcite, leaving the limestone beneath, carving a severe and treacherous landscape of deep canyons, caves, fissures, and these towering spires that can reach heights over 300 feet.

And we find the Madagascar Banana within these canyons, between these peaks, in a kind of microclimate where humidity is higher, soils are denser and more nutrient rich, and plant life is better protected from fire than in the surrounding savannas.

This is Dry Deciduous Forest, with distinct wet and dry seasons. The rainy season is November to March and sees up to 60 inches of precipitation. The dry season is from April to October, during which many plants, like our Banana, shed their leaves to prevent transpiration, and conserve water and resources. Annual temperatures at the Tsingy average in the 80s°F and can peak above the high 90°s.

The Madagascar Banana shares this rocky home with:

Leaf-tailed Gecko, West Coast Ebony, Madagascar Crested Ibis, Tsingy Wood Rail, Ghost Orchid, Red-fronted Brown Lemur, Pale Fork-marked Lemur, Screw Pine, Fossa, Heron, Flame Tree, Fony Baobab, Madagascar Rosewood, Madagascan Fruit Bat, Madagascar Palm, Tsingy Aloe, Western Bamboo Lemur, Bemaraha Bamboo, Ring-tailed Mongoose, Madagascar Fish Eagle, Madagascar Lace Plant, Rufous Trident Bat, Armoured Leaf Chameleon, Sifaka Lemur, and many many more.

Threats

Historically the Madagascar Banana population has been reduced by human habitat destruction. Specifically the conversion of dry forests for agriculture, growing maize and cassava, and cleared for pasturelands for cattle.

Slash-and-burn farming is particularly problematic. While, under normal conditions, the mature Madagascar Banana is fire tolerant; frequent, high-intensity human-induced fire destroys seedlings and young plants that have not yet developed their thick, protective pseudostem.

The extinction of animal species is an historic and ongoing threat to the Madagascar Banana’s survival. The island was once populated with multiple species of very large lemur, Sloth Lemur, Koala Lemur, Giant-ruffed Lemur, who were likely seed dispersers of the Madagascar Banana. But following the arrival of humans on Madagascar, and due to human hunting and habitat destruction, the large lemurs are now extinct.

Losing these seed-dispersing lemurs reduces the reproductive success of the Madagascar Banana. As mentioned it’s monocarpic, they only flower and fruit once, a whole lifecycle resulting in a singular abundance of fruit and seed. That today fruits into a habitat with less beings to receive and distribute it.

Lastly, human-induced climate change due to persistent overreliance on fossil fuels, threatens the Madagascar Banana. As global temperatures rapidly rise, the island’s dry season is getting longer and more intense. These are months in which the plant is not photosynthesizing, not producing new energy, and so as that time lengthens that increases the possibility that stored energy reserves might run out, resulting in death.

Conservation

Fortunately, most of the known remaining population of Madagascar Banana are found within protected areas, in the Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park and the Anka-rana Special Reserve, providing protection against logging and clearing. Additionally, conservationists in these reserves are focusing on fire management, creating firebreaks for example, and working with local communities to reduce the frequency of wildfire.

The Kew Royal Botanic Gardens has collected seeds from the few remaining wild individuals that are now conserved in the Millennium Seed Bank. And there are living individuals in botanical gardens in Kenya and Italy.

The Madagascar Banana has been considered critically endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2018 and their population is currently in decline.

Our most recent counts estimate that less than 5 Madagascar Banana remain in the wild.

Citations 21:33

Information for today’s show about the Madagascar Banana was compiled from:

Allen, R. 2018. Ensete perrieri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T98249345A98249347. – https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T98249345A98249347.en

Allen, Richard; Clarkson, James J; Ralimanana, Hélène (6 July 2018). “The critically endangered Madagascar Banana”. Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. - https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/madagascan-banana

Borrell, James S et al. “Enset in Ethiopia: a poorly characterized but resilient starch staple.” Annals of Botany v.123, no.5 (2019): 747-766. - https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcy214

Grubb, Peter J. “Interpreting some outstanding features of the flora and vegetation of Madagascar.” Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics v.6 no.1-2. p 125-146. 2003. – https://doi.org/10.1078/1433-8319-00046

Humbert, H., and Jean-François Leroy. 1936. Flore de Madagascar et Des Comores : Plantes Vasculaires. Tananarive: Imprimerie officielle. – https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/8099122

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). Andrefana Dry Forests - 2025 Conservation Outlook Assessment. IUCN World Heritage Outlook. October 11, 2025. – https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/explore-sites/andrefana-dry-forests

Musée colonial de Marseille. 1907. Annales du Muśee colonial de Marseille. Vol. ser. 2 v. 7. Marseille: Faculté des sciences de Marseille, Musée colonial. – https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/45311062

UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre. World Heritage Datasheet: Tsingy De Bemaraha Strict Nature Reserve. - http://world-heritage-datasheets.unep-wcmc.org/datasheet/output/site/tsingy-de-Bemaraha-strict-nature-reserve/

Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park. Madagascar National Parks. - https://parcs-madagascar.com/en/parc/tsingy-de-Bemaraha-2/

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ensete_perrieri

Music 22:58

Pledge 29:37

I honor the lifeforce of the Madagascar Banana. I will commit its name to my record. I am grateful to have shared time on our planet with this being. I lament the ways in which I and my species have harmed and diminished this species. I grieve.

And so, in the name of the Madagascar Banana I pledge to reduce my consumption. And my carbon footprint. And curb my wastefulness. I pledge to acknowledge and attempt to address the costs of my actions and inactions. And I pledge to resist the harm of plant and animal kin and their habitat, by individuals, corporations, and governments.

I forever pledge my song to the witness and memory of all life, to a broad celebration of biodiversity, and to the total liberation of all beings.